Reinforcement Learning

for Improving Agent Design

Abstract

In many reinforcement learning tasks, the goal is to learn a policy to manipulate an agent, whose design is fixed, to maximize some notion of cumulative reward. The design of the agent's physical structure is rarely optimized for the task at hand. In this work, we explore the possibility of learning a version of the agent's design that is better suited for its task, jointly with the policy. We propose a minor modification to the Gym

Introduction

Embodied cognition

While evolution shapes the overall structure of the body of a particular species, an organism can also change and adapt its body to its environment during its life. For instance, professional athletes spend their lives body training while also improving specific mental skills required to master a particular sport

We are interested to investigate embodied cognition within the reinforcement learning (RL) framework. Most baseline tasks

Furthermore, we believe the ability to learn useful morphology is an important area for the advancement of AI. Although morphology learning originally initiated from the field of evolutionary computation, there has also been great advances in RL in recent years, and we believe much of what happens in ALife should be in principle be of interest to the RL community and vice versa, since learning and evolution are just two sides of the same coin.

We believe that conducting experiments using standardized simulation environments facilitate the communication of ideas across disciplines, and for this reason we design our experiments based on applying ideas from ALife, namely morphology learning, to standardized tasks in the OpenAI Gym environment, a popular testbed for conducting experiments in the RL community. We decide to use standardized Gym environments such as Ant (based on Bullet physics engine) and Bipedal Walker (based on Box2D) not only for their simplicity, but also because their difficulty is well-understood due to the large number of RL publications that use them as benchmarks. As we shall see later, the BipedalWalkerHardcore-v2 task, while simple looking, is especially difficult to solve with modern Deep RL methods. By applying simple morphology learning concepts from ALife, we are able to make a difficult task solvable with much fewer compute resources. We also made the code for augmenting OpenAI Gym for morphology learning, along with all pretrained models for reproducing results in this paper available.

We hope this paper can serve as a catalyst to precipitate a cultural shift in both fields and encourage researchers to open up our minds to each other. By drawing ideas from ALife and demonstrating them in the OpenAI Gym platform used by RL, we hope this work can set an example to bring both the RL and ALife communities closer together to find synergies and push the AI field forward.

Related Work

There is a broad literature in evolutionary computation, artificial life and robotics devoted to studying, and modelling embodied cognition

Literature in the area of passive dynamics study robot designs that rely on natural swings of motion of body components instead of deploying and controlling motors at each joint

Recent works in robotics investigate simultaneously optimizing body design and control of a legged robot

Method

In this section, we describe the method used for learning a version of the agent's design better suited for its task jointly with its policy. In addition to the weight parameters of our agent's policy network, we will also parameterize the agent's environment, which includes the specification of the agent's body structure. This extra parameter vector, which may govern the properties of items such as width, length, radius, mass, and orientation of an agent's body parts and their joints, will also be treated as a learnable parameter. Hence the weights we need to learn will be the parameters of the agent's policy network combined with the environment's parameterization vector. During a rollout, an agent initialized with will be deployed in an environment that is also parameterized with the same parameter vector .

The goal is to learn to maximize the expected cumulative reward, , of an agent acting on a policy with parameters in an environment governed by the same . In our approach, we search for using a population-based policy gradient method based on Section 6 of Williams' 1992 REINFORCE

Armed with the ability to change the design configuration of an agent's own body, we also wish to explore encouraging the agent to challenge itself by rewarding it for trying more difficult designs. For instance, carrying the same payload using smaller legs may result in a higher reward than using larger legs. Hence the reward given to the agent may also be augmented according to its parameterized environment vector. We will discuss reward augmentation to optimize for desirable design properties later on in more detail later on.

Overview of Population-based Policy Gradient Method (REINFORCE)

In this section we provide an overview of the population-based policy gradient method described in Section 6 of William's REINFORCE

Using the log-likelihood trick allows us to write the gradient of with respect to :

In a population size of , where we have solutions , , ..., , we can estimate this as:

With this approximated gradient , we then can optimize using gradient ascent:

and sample a new set of candidate solutions from updating the pdf using learning rate . We follow the approach in REINFORCE where is modelled as a factored multi-variate normal distribution. Williams derived closed-form formulas of the gradient . In this special case, will be the set of mean and standard deviation parameters. Therefore, each element of a solution can be sampled from a univariate normal distribution . Williams derived the closed-form formulas for the term for each individual and element of vector on each solution in the population:

.

For clarity, we use subscript , to count across parameter space in , and this is not to be confused with superscript , used to count across each sampled member of the population of size . Combining the last two equations, we can update and at each generation via a gradient update.

We note that there is a connection between population-based REINFORCE, a population-based policy gradient method, and particular formulations of Evolution Strategies

Experiments

Learning better legs for better gait

RoboschoolAnt-v1

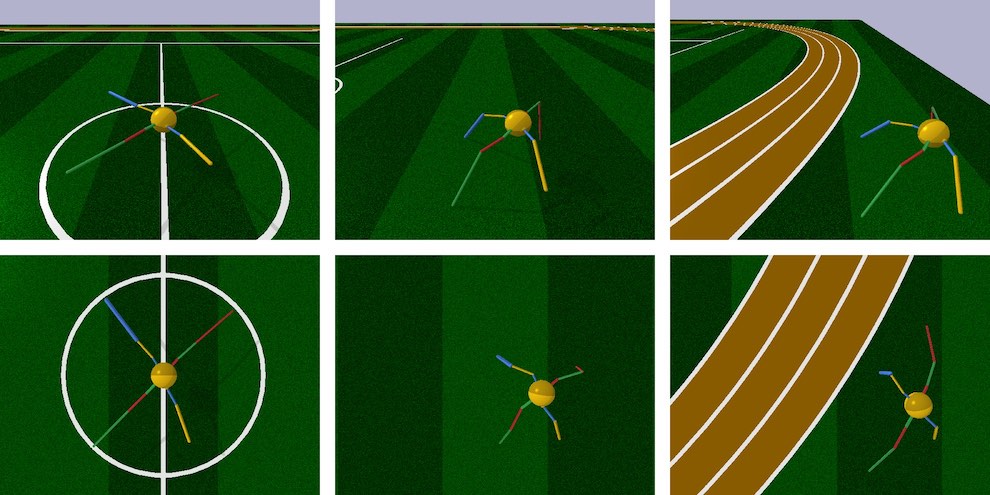

In this work, we experiment on continuous control environments from Roboschool

The RoboschoolAnt-v1

In our experiment, we keep the volumetric mass density of all materials, along with the parameters of the motor joints identical to the original environment, and allow the 36 parameters (3 parameters per leg part, 3 leg parts per leg, 4 legs in total) to be learned. In particular, we allow each part to be scaled to a range of 75% of its original value. This allows us to keep the sign and direction for each part to preserve the original intended structure of the design.

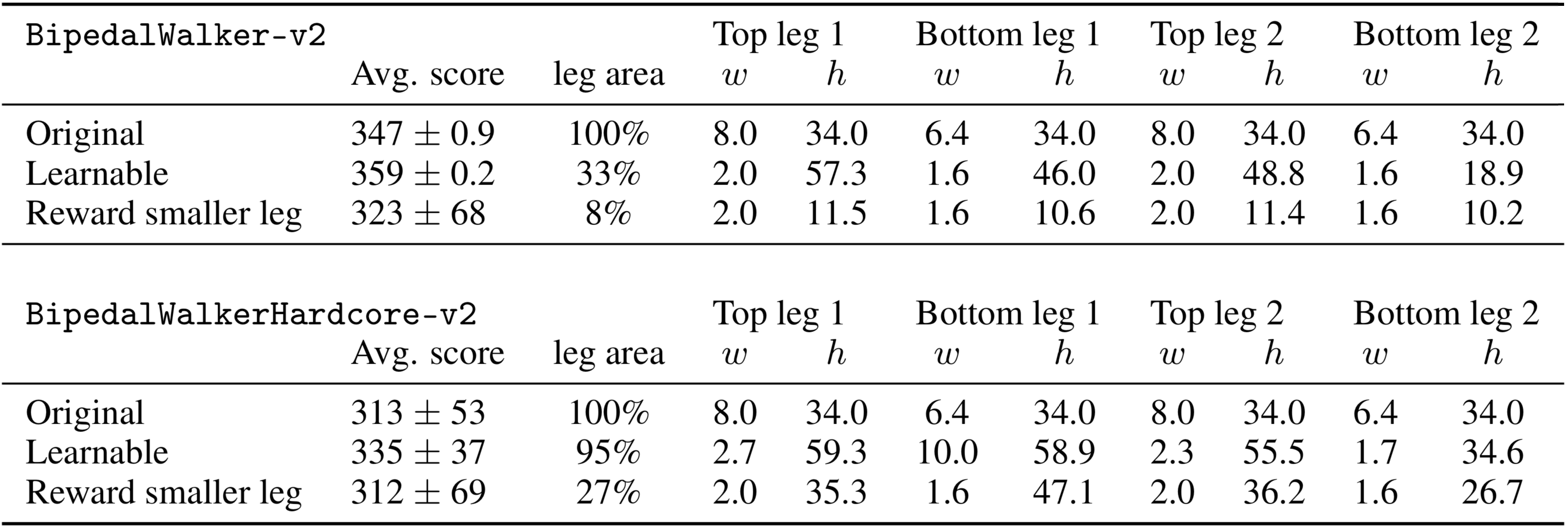

The above figure illustrates the learned agent design compared to the original design. With the exception of one leg part, it learns to develop longer, thinner legs while jointly learning to carry the body across the environment. While the original design is symmetric, the learned design breaks symmetry, and biases towards larger rear legs while jointly learning the navigation policy using an asymmetric body. The original agent achieved an average cumulative score of 3447 251 over 100 trials, compared to 5789 479 for an agent that learned a better body design.

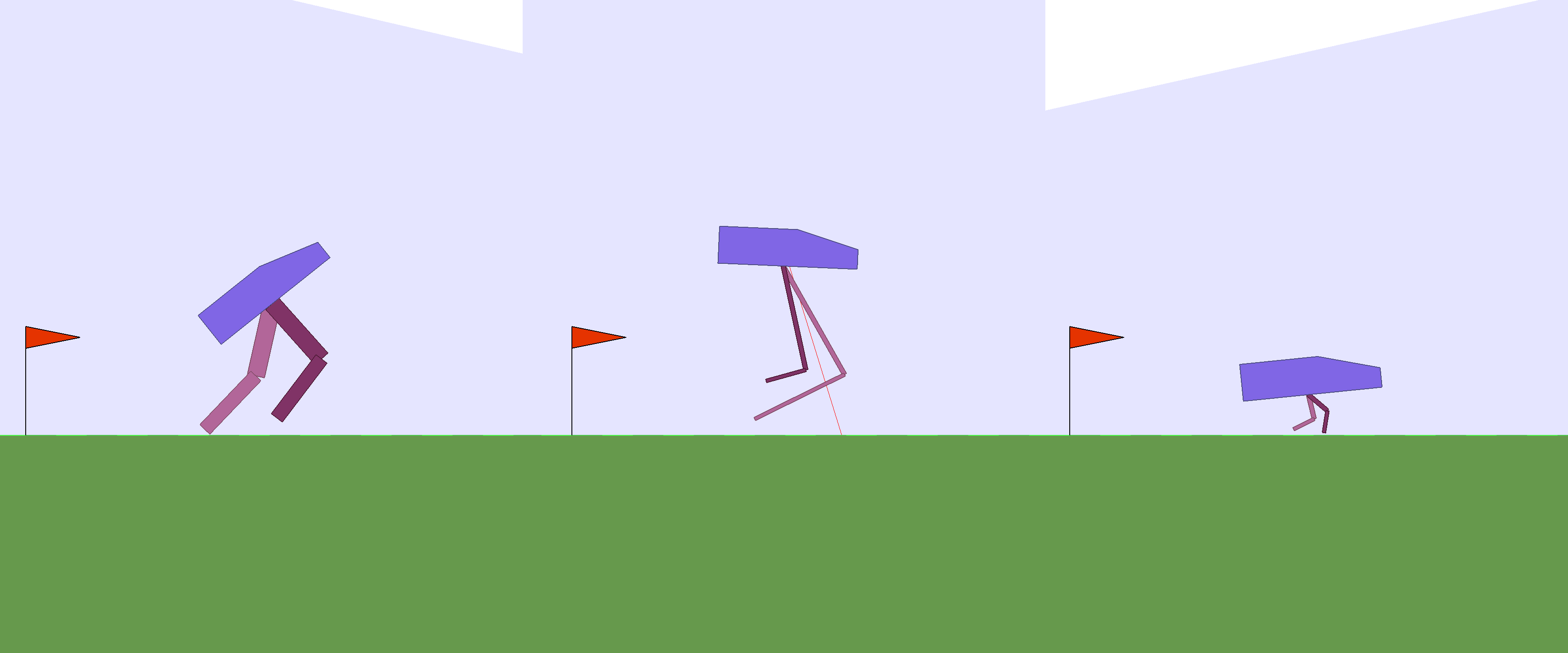

BipedalWalker-v2

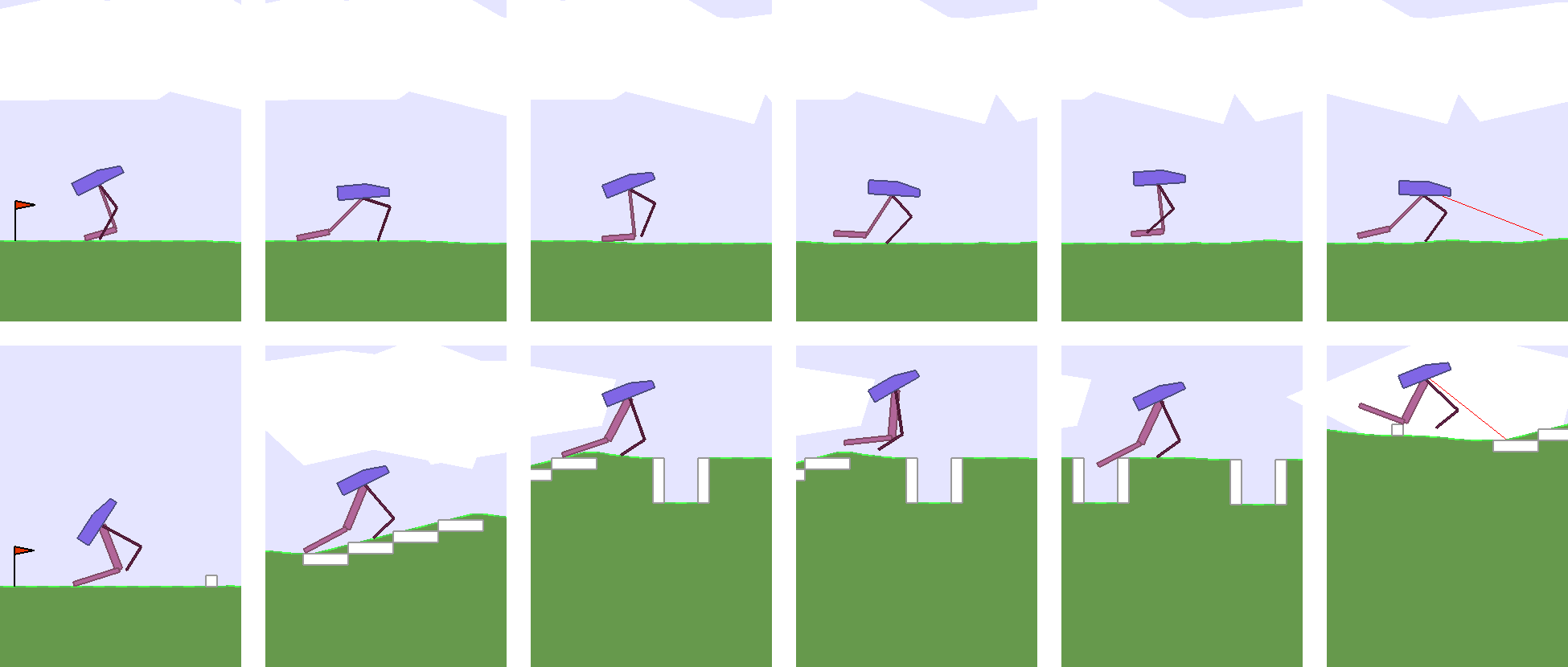

The Bipedal Walker series of environments is based on the Box2D

Keeping the head payload constant, and also keeping the density of materials and the configuration of the motor joints the same as the original environment, we only allow the lengths and widths for each of the 4 leg parts to be learnable, subject to the same range limit of 75% of the original design. In the original environment, the agent learns a policy that is reminiscent of a joyful skip across the terrain, achieving an average score of 347. In the learned version, the agent's policy is to hop across the terrain using its legs as a pair of springs, achieving a higher average score of 359.

In our experiments, all agents were implemented using 3 layer fully-connected networks with activations. The agent in RoboschoolAnt-v1 has 28 inputs and 8 outputs, all bounded between and , with hidden layers of 64 and 32 units. The agents in BipedalWalker-v2 and BipedalWalkerHardcore-v2 has 24 inputs and 4 outputs all bounded between and , with 2 hidden layers of 40 units each.

Our population-based training experiments were conducted on 96-CPU core machines. Following the approach described in

Joint learning of body design facilitates policy learning

BipedalWalkerHardcore-v2

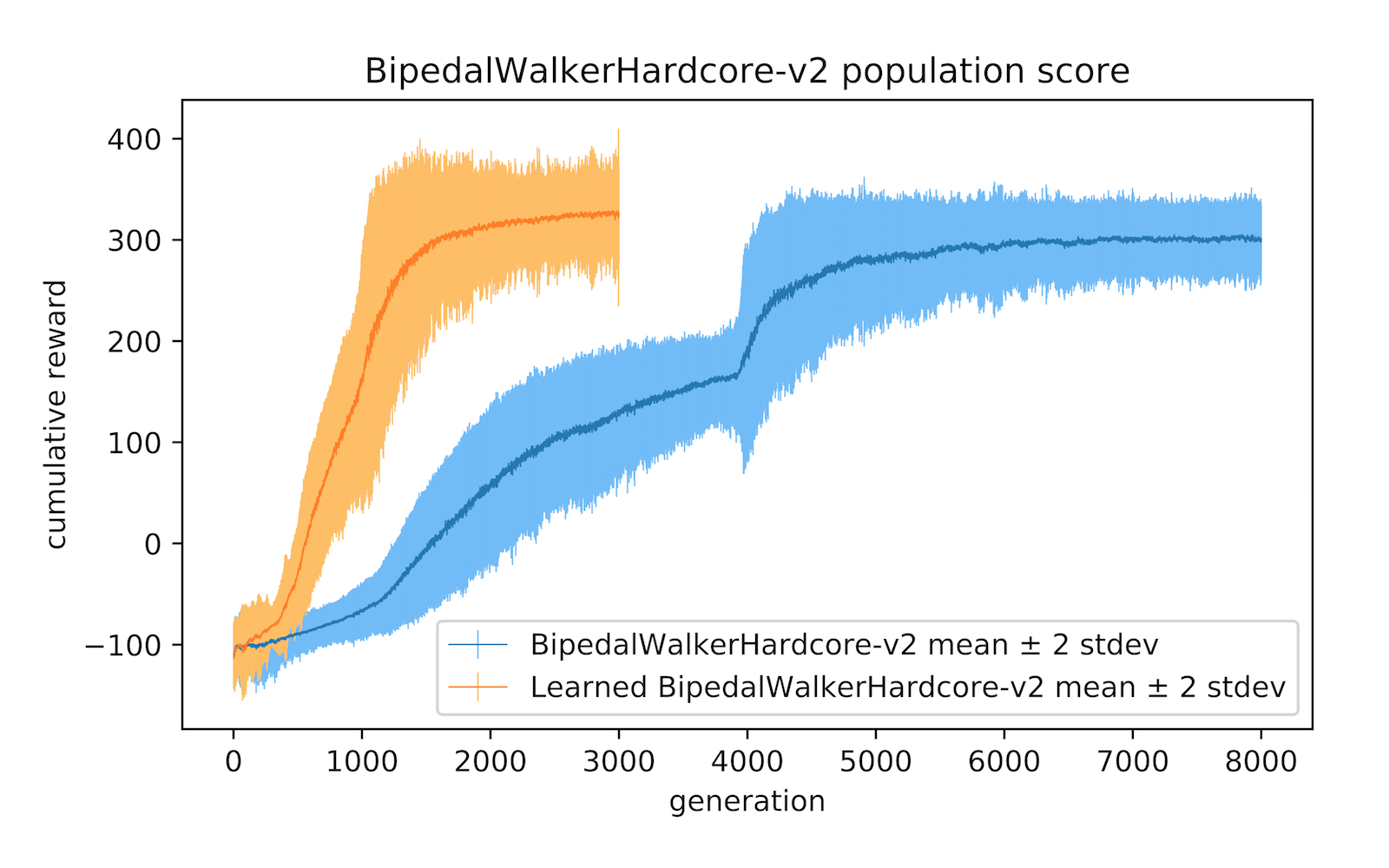

Learning a better version of an agent's body not only helps achieve better performance, but also enables the agent to jointly learn policies more efficiently. We demonstrate this in the much more challenging BipedalWalkerHardcore-v2

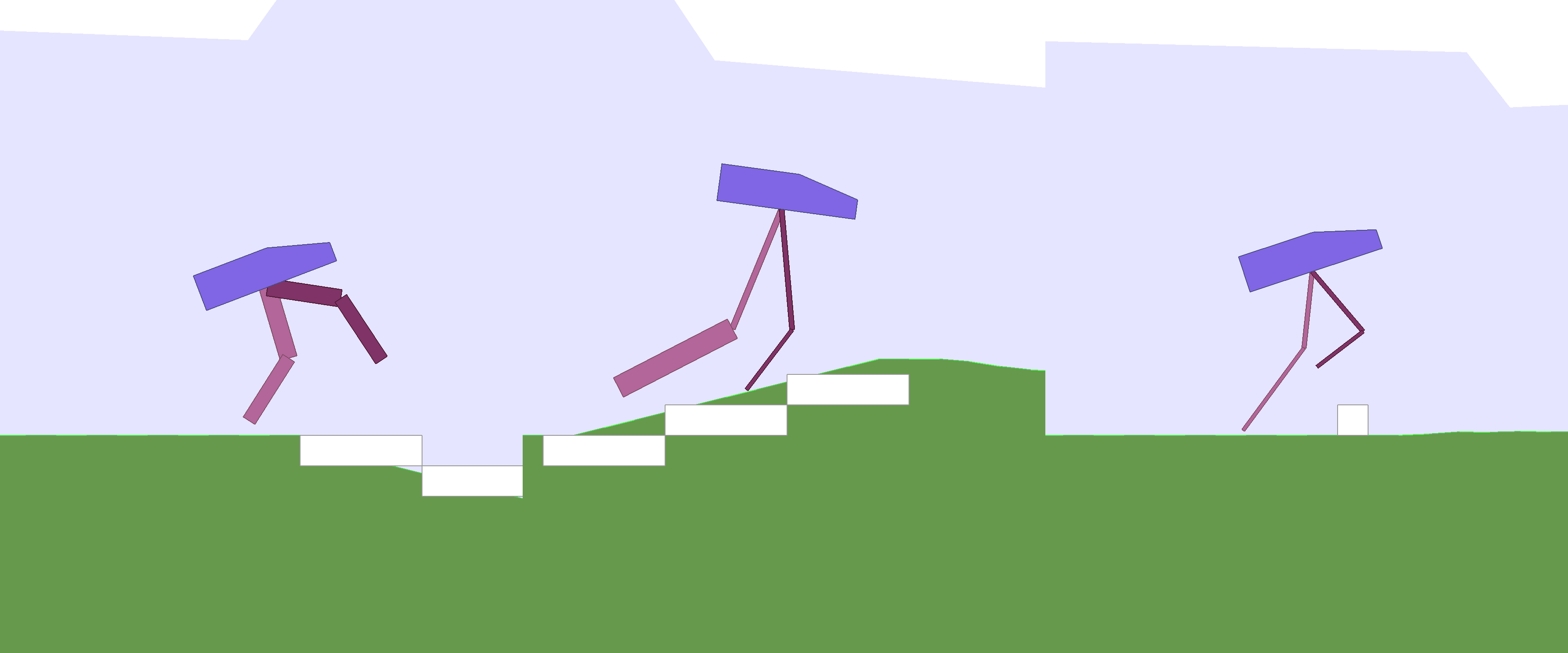

In this environment, our agent generally learns to develop longer, thinner legs, with the exception in the rear leg where it developed a thicker lower limb to serve as useful stability function for navigation. Its front legs, which are smaller and more manoeuvrable, also act as a sensor for dangerous obstacles ahead that complement its LIDAR sensors. While learning to develop this newer structure, it jointly learns a policy to solve the task in 30% of the time it took the original, static version of the environment. The average scores over 100 rollouts for the learnable version is 335 37 compared to the baseline score of 313 53.

Optimize for both the task and desired design properties

Allowing an agent to learn a better version of its body obviously enables it to achieve better performance. But what if we want to give back some of the additional performance gains, and also optimize also for desirable design properties that might not generally be beneficial for performance? For instance, we may want our agent to learn a design that utilizes the least amount of materials while still achieving satisfactory performance on the task. Here, we reward an agent for developing legs that are smaller in area, and augment its reward signal during training by scaling the rewards by a utility factor of . We see that augmenting the reward encourages development of smaller legs:

This reward augmentation resulted in much a smaller agent that is still able to support the same payload. In the easier BipedalWalker task, given the simplicity of the task, the agent's leg dimensions eventually shrink to near the lower bound of 25% of the original dimensions, with the exception of the heights of the top leg parts which settled at 35% of the initial design, while still achieving an average (unaugmented) score of 323 68. For this task, the leg area used is 8% of the original design.

However, the agent is unable to solve the more difficult BipedalWalkerHardcore task using a similar small body structure, due to the various obstacles presented. Instead, it learns to set the widths of each leg part close to the lower bound, and instead learn the shortest heights of each leg part required to navigate, achieving a score of 312 69. Here, the leg area used is 27% of the original.

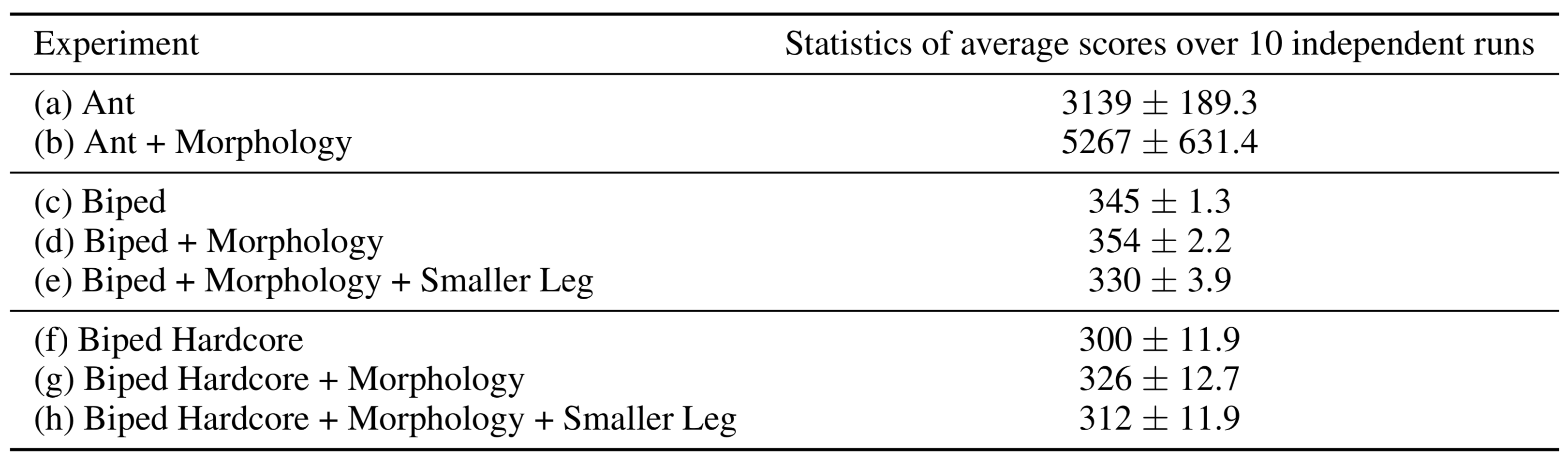

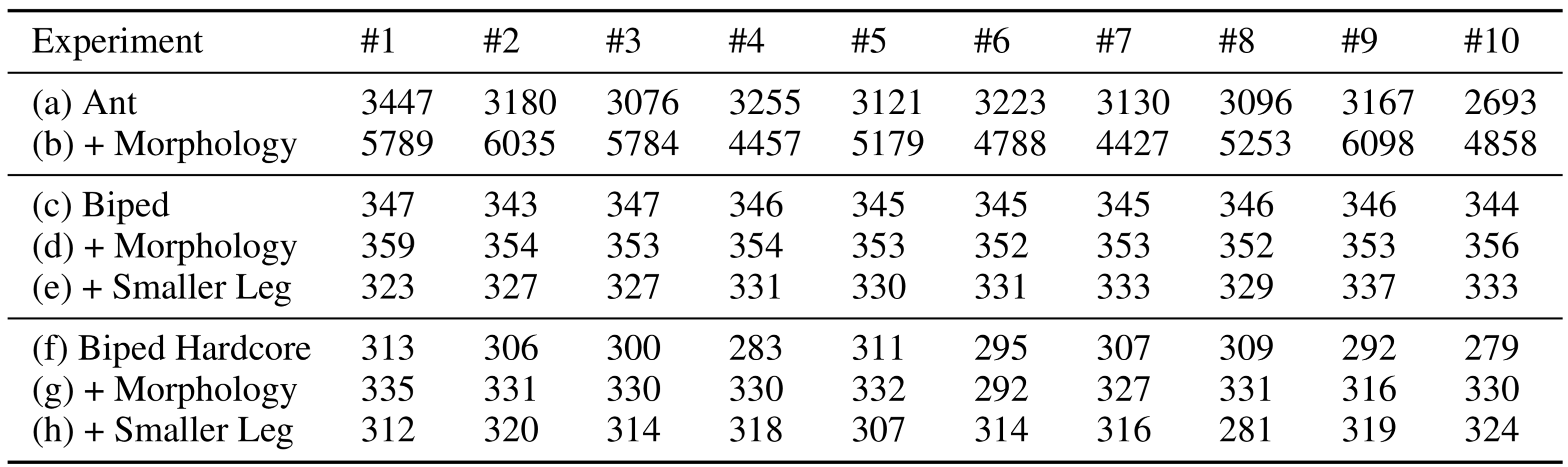

Results over Multiple Experimental Runs

In the previous sections, for simplicity, we have presented results over a single representative experimental run to convey qualitative results such as morphology description corresponding to average score achieved. Running the experiment from scratch with a different random seed may generate different morphology designs and different policies that lead to different performance scores. To demonstrate that morphology learning does indeed improve the performance of the agent over multiple experimental runs, we run each experiment 10 times and report the full range of average scores obtained in the two tables below:

From multiple independent experimental runs, we see that morphology learning consistently produces higher scores over the normal task.

We also visualize the variations of morphology designs over different runs in the following figure to get a sense of the variations of morphology that can be discovered during training:

As these models may take up to several days to train for a particular experiment on a powerful 96-core CPU machine, it may be costly for the reader to fully reproduce the variation of results here, especially when 10 machines running the same experiment with different random seeds are required. We also include all pretrained models from multiple independent runs in the GitHub repository containing the code to reproduce this paper. The interested reader can examine the variations in more detail using the pretrained models.

Discussion and Future Work

We have shown that allowing a simple population-based policy gradient method to learn not only the policy, but also a small set of parameters describing the environment, such as its body, offer many benefits. By allowing the agent's body to adapt to its task within some constraints, it can learn policies that are not only better for its task, but also learn them more quickly.

The agent may discover design principles during this process of joint body and policy learning. In both RoboschoolAnt and BipedalWalker experiments, the agent has learned to break symmetry and learn relatively larger rear limbs to facilitate their navigation policies. While also optimizing for material usage for BipedalWalker's limbs, the agent learns that it can still achieve the desired task even by setting the size of its legs to the minimum allowable size. Meanwhile, for the much more difficult BipedalWalkerHardcore-v2 task, the agent learns the appropriate length of its limbs required for the task while still minimizing the material usage.

This approach may lead to useful applications in machine learning-assisted design, in the spirit of

In this work we have only explored using a simple population-based policy gradient method

Separation of policy learning and body design into inner loop and outer loop will also enable the incorporation of evolution-based approaches to tackle the vast search space of morphology design, while utilizing efficient RL-based methods for policy learning. The limitations of the current approach is that our RL algorithm can learn to optimize only existing design properties of an agent's body, rather than learn truly novel morphology in the spirit of Karl Sims' Evolving Virtual Creatures

Nevertheless, our approach of optimizing the specifications of an existing design might be more practical for many applications. An evolutionary algorithm might come up with trivial designs and corresponding simple policies that outperform designs we actually want -- for instance, a large ball that rolls forward will easily outperforming the best bipedal walkers, but this might not be useful to a game designer who simply wants to optimize the dimensions of an existing robot character for a video game. Due to the vast search space of morphology, a search algorithm can easily come up with a trivial, but unrealistic or unusable design that exploits its simulation environment

Just as REINFORCE

Bloopers

For those of you who made it this far, we would like to share some “negative results” of things that we tried but didn't work. In the experiments, we constrain the elements in the modified design to be 75% of the original design's values. We accomplish this by defining a scaling factor for each learnable parameter as where is the element of the environment parameter vector, and multiply this scaling factor to the original design's value, and find that this approach works well as it usually preserves the intention and essence of the original design.

We also tried to let the RL algorithm discover new designs without any constraints, and found that it would usually create longer rear legs during the initial learning phase designed so it can tumble over further down the map to achieve higher rewards.

Using a lognormal scaling factor of made it easier for the RL algorithm to come up with an extremely tall bipedal walker agent that “solves” the task by simply falling over and landing at the exit: